The slang of the Poilus, the language of the trenches

I n August 1914, millions of men from a wide variety of social, professional and cultural backgrounds were called up. The general mobilization then generates an unprecedented cultural mix. Each mobilized has a patois, a culture, traditions specific to his region or his profession.

Troops mobilized in the army zone are subject to extreme conditions. The fighters need adapted words to think, to translate these upheavals and to communicate with the rear. The homeland, for its part, needs to be reassured about the fate of its children.

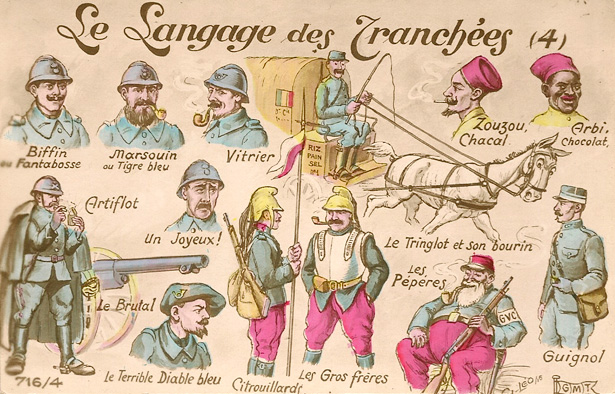

Slang is a marker of belonging to the community of combat troops. This one also gives, vis-à-vis the back, relief to a daily life often characterized by boredom and repetition. Finally, it allows hairy people to distance themselves from the violent aspects and the harshness of their condition.

The vocabulary alternately borrows words from the military world or from provincial slang. It is also the time when words known in the colonies since the 19th century are widely disseminated.

D uring the conflict, lexicons of the vocabulary of the soldiers appeared to inform the rear, which was unaware of life at the front. Some authors of these come from the world of fighters.

The literature on the subject of the Great War will also use these terms from the trenches. Many will enter the dictionaries after the conflict.

A century later, many of these terms have now passed into everyday language and we use them without knowing their roots in the mud of the trenches.

The exhibition is visible during the museum’s usual hours until August 26, 2022.